This post is a part of a series on drug shortages.

In the Part 1 I summarised my work to characterize the extents of drug shortages in Canada. In this part, I move on to summarising my work to look at the impact those shortages may have on the health care system. At the end of this post I summarize my findings, mention some obvious gaps to fill, and discuss some possible next steps.

The impact of drug shortages

Drug shortages are, by definition, a disruption in the supply of medication to patients directly, pharmacies, health care providers, and other institutions. How should we assess the downstream impact of these supply disruptions? Tallying the number and kinds of shortages, as we have done, gives some sense of the extent of the problem but could be misleading. For instance, it’s conceivable that some shortages have no real downstream impact because, say, there is enough of a buffer of stock in the supply chain that they go unnoticed. Of course, it may also be that shortages lead to varying degrees of morbidity depending on how troublesome it is to miss a dose of a certain medication, or switch to an alternate medication, or knock-on shortages, or any of a myriad of other consequent complicating factors. There is a deep exploration of these downstream effects to be done, but I did not do that.

Instead, I looked at two facets (proxies, you could say) for downstream impact. The first is a look at shortages of frequently prescribed and crucial medications listed on a proposed Essential Medicines list for Canada. The second is a case study into shortages of two particular medications for reflux, with the hope that such a deep dive can give us greater insight into the dynamics of shortages.

Essential medicines

The World Health Organisation uses the concept of an essential medicines list (EML) to capture critically important medications for the functioning of a health care system. Such a list is meant to focus the attention of governments and institutions in order to protect the supplies of the medications on it because they are deemed so valuable, and therefore shortages so disruptive.

Canada does not have an essential medicines list, but there has been recent work by Taglione et al., 2017 to build a Canadian edition of an essential medicine list (see also cleanmeds.ca) by searching prescription records to identify frequently prescribed medications, and also includes those judged to be crucial by Canadian physicians. The list includes 126 different medications. By dint of the list’s construction, we should expect shortages of these medications to cause significant morbidity and disruption to care, and perhaps more so than than a shortage of any randomly selected non-list medication.

Looking at the shortage data, I found that in 2019 all of the drugs on the essential medicines list were in shortage at some point during the year. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that each medication was entirely unavailable at some point, but just that at least one of the formulations (DIN) of each medication went into shortage. In addition, a quarter (24.3%) of the 2019 shortages were of drugs on the essential medicines list. Are these numbers surprising? It’s hard to say without knowing the base rates of shortages across other medications. I said I would avoid statistics, but in this situation it is warranted: the odds ratio of a drug (qua DIN) on the essential medicines list being in shortage compared to other drugs on the market is 1.52 (95% CI 1.38-1.70). That is, drugs on the essential medicines list are about 50% more likely to have a shortage than drugs not on the list.

My takeaways:

- Shortages regularly affect critical medications. Naively you might have thought that shortages primarily happen to the more rare and specialised drugs, perhaps thinking that commonly prescribed medications have the benefit of well-oiled manufacturing processes and supply chains or some other layer of protection. No dice. If shortages have deleterious downstream effects on health, this analysis shows clearly that they happen to medications thought to need the mos protection from shortages. Having said that, it’s an open question as to whether some medications have more resilience to shortages than others, and whether the essential medicines are of this kind. That is, even when a shortage happens to an essential medicine, perhaps these, more than other medications, are buffered by more manufacturers or greater alternatives or larger stockpiles. We will come back to this question in the “deep dive” in the next section.

- Shortages happen more often to critical medications. Now this is something I did not expect, and I’m not sure how to explain, but it is there in the data. I have yet to check previous years to see if this is a trend or not. If the trend holds then we really have to ask why EMLs are so disproportionately affected by shortages.

One thing we can answer immediately is whether there a subset of medications which are driving this disproportionality.

Yup, looks to be so. (For reference, the top five drugs from the EML with shortages are: Candesartan, diltiazem, ranitidine, pravastatin, and pantoprazole. The rest are left to you to look up.) More work will need to be done to really compare the essential medicines to non-essential medicines with respect to shortage rates (for instance, is the long tail of medications above also proportionately receiving more shortages?), but the aggregate observation still holds: essential medicines have more shortages in 2019 compared to non-essential medicines.

Deep dive into Ranitidine and Famotadine

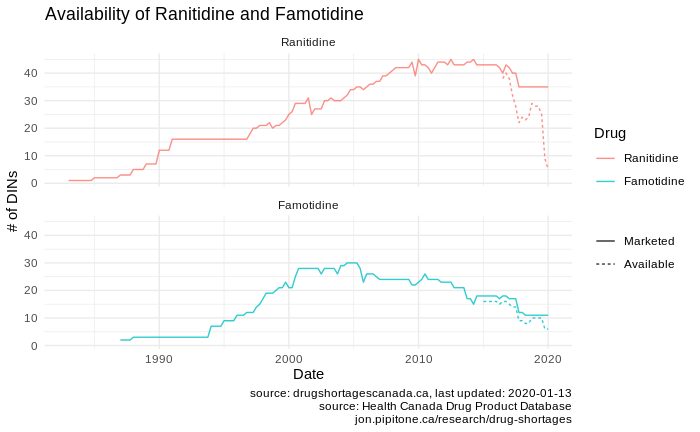

I won’t rehash the entire discussion here, but instead just point you to my post on the topic. The tl;dr is that we were approached by a CBC reporter about recent shortages of ranitidine and famotodine, two drugs used for reflux, and I dug into the data to see what, if anything, we could determine from the shortage reporting. Here’s what we found:

The availability of both ranitidine and famotidine have fallen over the last few years. Considering the figure above, we can see this is both an issue of a falling number of drugs on the market, worsened by significant shortages over the recent years for which we have shortage data (it’s worth noting that there may also have been significant shortages for these drugs pre-2017 when mandatory reporting came online).

One big open question is whether the shortage of one of these drugs was a factor in the subsequent shortage of the other… a so-called domino shortage. To answer this we can look at the reflux as a whole. The following chart shows the availability all of the medications have 10 or more formulations marketed over the last 10 years:

An obvious domino shortage doesn’t pop out at me qualitatively but perhaps this isn’t the most intuitive display to work from. It’s also difficult to tease apart the onset of new shortages with the onset of the availability of shortage reports. What do you think? A more in-depth analysis of domino shortages is warranted

But I do see this: There was no reactive increase in marketed drugs.. That is, the total number of medications for ulcers and reflux appears to essentially have been strictly falling over time. In my earlier post, I find evidence for this being driven by a drop in the number of manufacturers for these medications. Essentially, manufacturers are getting out of the game, and those that are producing medications in these classes are producing few formulations. I don’t have the context to understand why this is (is it the market optimising? is it a societal shift away from using these drugs in general? etc…), but regardless I would expect that as the pool of marketed drugs shrinks, the impact of any shortage of the remaining drugs may be worse because there is less “wiggle room” – there are few versions of drugs to switch to when a shortage occurs.

Lastly, in my earlier post I created some very detailed timelines of shortages and discontinuations for both ranitidine and famotidine. Go look at them again. I’ve made them clickable so you can view zoom in and actual read them now. Note that those timelines only show formulations that went into shortage so as to avoid cluttering the display (i.e. there are more formulations and manufacturers than are shown since not all of them have shortage reports).

Data Quality

Shifting gears for a moment, let’s talk about data quality in Drug Shortage Canada database. I did not intentionally set out to look at the data quality in the reporting but I ended up getting stung by data quality issues along the way and I think it’s worth noting these because they reflect on the conclusions we can draw from the data, as well as perhaps speak to how well manufacturers are doing with mandatory reporting.

I have to say that assessing data quality is hampered by the fact that there is no published data dictionary – there’s no reference for what the fields should contain and how to interpret them (e.g. what the heck is in the marker a1 or hc_updated_date fields?)

Anyhow, here are the issues I’ve come across so far:

- Mismatching ATCs. As I discussed in my post on the essential medicines list, the ATC codes listed in the DSC are often truncated or just don’t match what is in the Health Canada Drug Product Database (which I’m taking as an authoritative source).

- Missing/impossible shortage start/end dates. There are many examples of shortage reports that have started years ago that have no end date – are these actual shortages or just reports that also haven’t been properly updated? There are also several examples of reports that have start dates that are later than their end dates, and other date weirdness such as shortage reports for the same drug (DIN) that overlap with one another but that aren’t exactly duplicates (but there are those too).

- Conflicting shortage and discontinuation reports. You can see some of this in my post about one particular drug where shortages continue past the time when a discontinuation is reported. What does that mean? Is this another example of a shortage report that wasn’t updated, or is the discontinuation report incorrect.

There also may be some data quality issues in some of the other data sources I’ve used (for example, the ATC codes S01AA18 (polymyxin B), D01AE12 (salicylic acid), J01EE20 (Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) appear on the EML and in the WHO ATC database but not in the DPD) but I really didn’t dig into these very far.

In summary

So what have learned?

- Drug shortages impact essential medicines – the aren’t immune by dint of being popular or critically necessary – and it appears they are impacted more than non-essential medicines (this might be driven by some particularly shortage-prone medications on the list).

- In our deep-dive into the ranitidine and famotidine shortages we did not see any obvious indication of a domino shortage. Instead, we saw a shrinking pool of available reflux medications and fewer manufacturers.

- There are some obvious and problematic data quality with the drug shortages database. Some issues can be addressed (e.g. cross referencing ATC codes from the DPD) and others cannot (e.g. date fields) and these do impact the integrity of analysis. The DSC should, at the very least, publish a guide to interpreting their data.

The and next steps around assessing impact would be to do a more thorough analysis of possible “domino shortages”, perhaps by starting with a few case studies, as well as looking more closely into why the essential medicines are disproportionately prone to shortages. These two projects could likely dovetail nicely as they are both aimed at analysing shortage clusters. There is a larger project here (which I spoke about in my initial write up about project aims) around shortage prediction (e.g. if domino shortages exist, we could explore features that make these more or less likely and model shortage dynamics from that). Going beyond the shortage reporting data, I think impact ultimately needs to be assessed by tying the reported shortages to the actual downstream effects to patients and the health care system.